The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as a major component of many minerals such as limestone. Along with the nitrogen cycle and the water cycle, the carbon cycle comprises a sequence of events that are key to make Earth capable of sustaining life. It describes the movement of carbon as it is recycled and reused throughout the biosphere, as well as long-term processes of carbon sequestration to and release from carbon sinks.

The carbon cycle was discovered by Joseph Priestley and Antoine Lavoisier, and popularized by Humphry Davy.[2]

Main components

| Pool | Quantity (gigatons) |

|---|---|

| Atmosphere | 720 |

| Ocean (total) | 38,400 |

| Total inorganic | 37,400 |

| Total organic | 1,000 |

| Surface layer | 670 |

| Deep layer | 36,730 |

| Lithosphere | |

| Sedimentary carbonates | > 60,000,000 |

| Kerogens | 15,000,000 |

| Terrestrial biosphere (total) | 2,000 |

| Living biomass | 600 - 1,000 |

| Dead biomass | 1,200 |

| Aquatic biosphere | 1 - 2 |

| Fossil fuels (total) | 4,130 |

| Coal | 3,510 |

| Oil | 230 |

| Gas | 140 |

| Other (peat) | 250 |

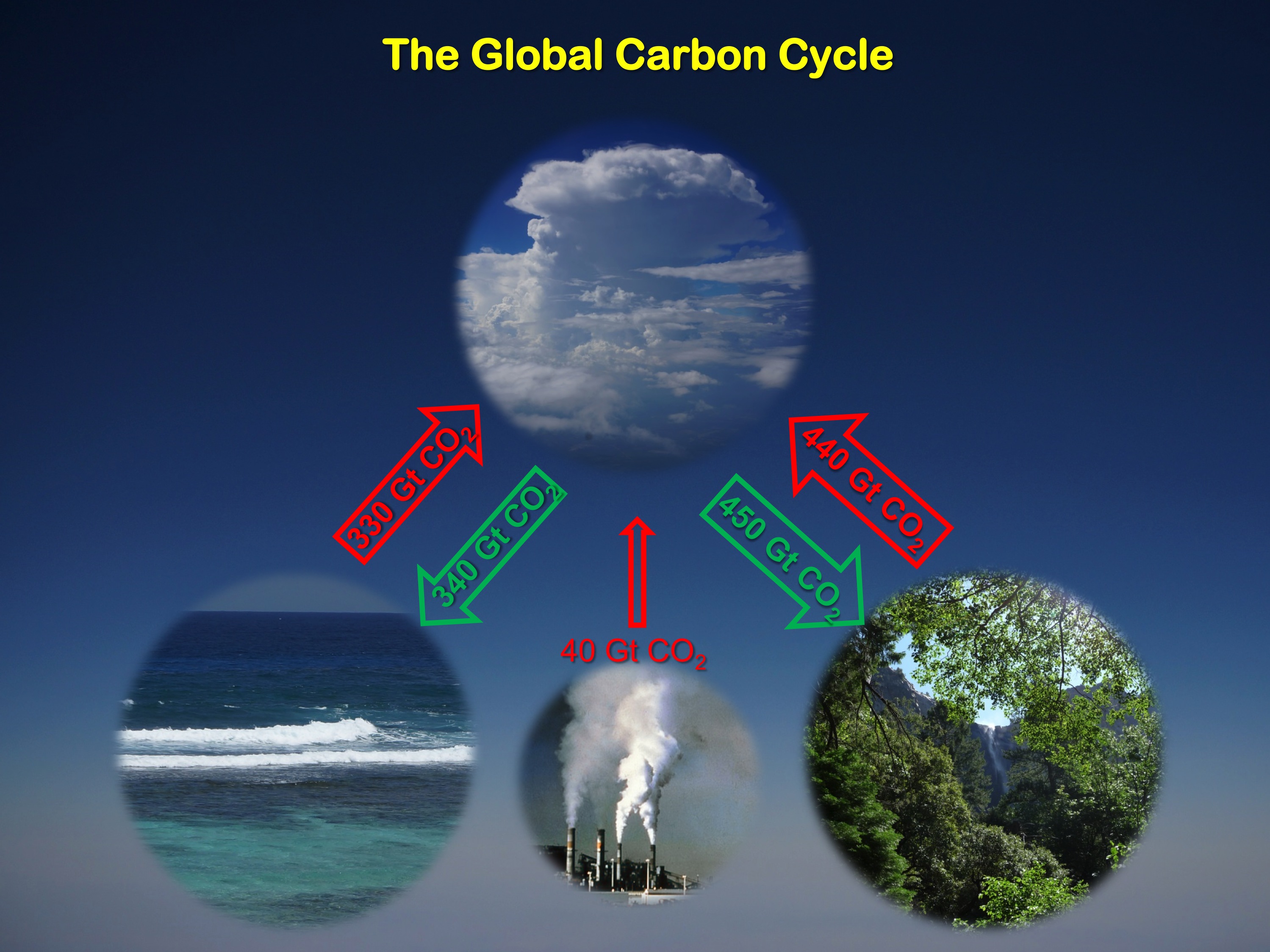

The global carbon cycle is now usually divided into the following major reservoirs of carbon interconnected by pathways of exchange:[4]:5–6

- The atmosphere

- The terrestrial biosphere

- The ocean, including dissolved inorganic carbon and living and non-living marine biota

- The sediments, including fossil fuels, freshwater systems, and non-living organic material.

- The Earth's interior (mantle and crust). These carbon stores interact with the other components through geological processes.

The carbon exchanges between reservoirs occur as the result of various chemical, physical, geological, and biological processes. The ocean contains the largest active pool of carbon near the surface of the Earth.[5] The natural flows of carbon between the atmosphere, ocean, terrestrial ecosystems, and sediments are fairly balanced so that carbon levels would be roughly stable without human influence.[6][7]

Atmosphere[edit]

2 and water from the atmosphere for living and growing.

Carbon in the Earth's atmosphere exists in two main forms: carbon dioxide and methane. Both of these gases absorb and retain heat in the atmosphere and are partially responsible for the greenhouse effect.[9] Methane produces a larger greenhouse effect per volume as compared to carbon dioxide, but it exists in much lower concentrations and is more short-lived than carbon dioxide, making carbon dioxide the more important greenhouse gas of the two.[10]

Carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere primarily through photosynthesis and enters the terrestrial and oceanic biospheres. Carbon dioxide also dissolves directly from the atmosphere into bodies of water (ocean, lakes, etc.), as well as dissolving in precipitation as raindrops fall through the atmosphere. When dissolved in water, carbon dioxide reacts with water molecules and forms carbonic acid, which contributes to ocean acidity. It can then be absorbed by rocks through weathering. It also can acidify other surfaces it touches or be washed into the ocean.[11]

Human activities over the past two centuries have significantly increased the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, mainly in the form of carbon dioxide, both by modifying ecosystems' ability to extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and by emitting it directly, e.g., by burning fossil fuels and manufacturing concrete.[12]

In the extremely far future, the carbon cycle will likely speed up the rate of carbon dioxide is absorbed into the soil from carbonate–silicate cycle. This is mainly caused by the increased luminosity of the Sun, which speeds up the rate of surface weathering.[13] This will eventually cause most of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to be squelched into the Earth's crust as carbonate. Though volcanoes will continue to pump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in the short term, it will not be enough to keep the carbon dioxide level stable in the long term.[14][full citation needed] Once the carbon dioxide level falls below 50 particles per million, C3 photosynthesis will no longer be possible. This is expected to occur about 600 million years from now.[citation needed]

Once the oceans on the Earth evaporate in about 1.1 billion years from now,[1] plate tectonics will very likely stop due to the lack of water to lubricate them. The lack of volcanoes pumping out carbon dioxide will cause the carbon cycle to end between 1 billion and 2 billion years into the future.[2][full citation needed]

Terrestrial biosphere[edit]

The terrestrial biosphere includes the organic carbon in all land-living organisms, both alive and dead, as well as carbon stored in soils. About 500 gigatons of carbon are stored above ground in plants and other living organisms,[3] while soil holds approximately 1,500 gigatons of carbon.[4] Most carbon in the terrestrial biosphere is organic carbon,[5] while about a third of soil carbon is stored in inorganic forms, such as calcium carbonate.[6] Organic carbon is a major component of all organisms living on earth. Autotrophs extract it from the air in the form of carbon dioxide, converting it into organic carbon, while heterotrophs receive carbon by consuming other organisms.

Because carbon uptake in the terrestrial biosphere is dependent on biotic factors, it follows a diurnal and seasonal cycle. In CO

2 measurements, this feature is apparent in the Keeling curve. It is strongest in the northern hemisphere because this hemisphere has more land mass than the southern hemisphere and thus more room for ecosystems to absorb and emit carbon.

Carbon leaves the terrestrial biosphere in several ways and on different time scales. The combustion or respiration of organic carbon releases it rapidly into the atmosphere. It can also be exported into the ocean through rivers or remain sequestered in soils in the form of inert carbon.[7] Carbon stored in soil can remain there for up to thousands of years before being washed into rivers by erosion or released into the atmosphere through soil respiration. Between 1989 and 2008 soil respiration increased by about 0.1% per year.[8] In 2008, the global total of CO

2 released by soil respiration was roughly 98 billion tonnes, about 10 times more carbon than humans are now putting into the atmosphere each year by burning fossil fuel (this does not represent a net transfer of carbon from soil to atmosphere, as the respiration is largely offset by inputs to soil carbon). There are a few plausible explanations for this trend, but the most likely explanation is that increasing temperatures have increased rates of decomposition of soil organic matter, which has increased the flow of CO

2. The length of carbon sequestering in soil is dependent on local climatic conditions and thus changes in the course of climate change.

Ocean[edit]

The ocean can be conceptually divided into a surface layer within which water makes frequent (daily to annual) contact with the atmosphere, and a deep layer below the typically mixed layer depth of a few hundred meters or less, within which the time between consecutive contacts may be centuries. The dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the surface layer is exchanged rapidly with the atmosphere, maintaining equilibrium. Partly because its concentration of DIC is about 15% higher[9] but mainly due to its larger volume, the deep ocean contains far more carbon—it's the largest pool of actively cycled carbon in the world, containing 50 times more than the atmosphere[10]—but the timescale to reach equilibrium with the atmosphere is hundreds of years: the exchange of carbon between the two layers, driven by thermohaline circulation, is slow.[11]

Carbon enters the ocean mainly through the dissolution of atmospheric carbon dioxide, a small fraction of which is converted into carbonate. It can also enter the ocean through rivers as dissolved organic carbon. It is converted by organisms into organic carbon through photosynthesis and can either be exchanged throughout the food chain or precipitated into the ocean's deeper, more carbon-rich layers as dead soft tissue or in shells as calcium carbonate. It circulates in this layer for long periods of time before either being deposited as sediment or, eventually, returned to the surface waters through thermohaline circulation.[12] Oceans are basic (~pH 8.2), hence CO

2 acidification shifts the pH of the ocean towards neutral.

Oceanic absorption of CO

2 is one of the most important forms of carbon sequestering limiting the human-caused rise of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. However, this process is limited by a number of factors. CO

2 absorption makes water more acidic, which affects ocean biosystems. The projected rate of increasing oceanic acidity could slow the biological precipitation of calcium carbonates, thus decreasing the ocean's capacity to absorb carbon dioxide.[13][1]

Geosphere[edit]

The geologic component of the carbon cycle operates slowly in comparison to the other parts of the global carbon cycle. It is one of the most important determinants of the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, and thus of global temperatures.[2]

Most of the earth's carbon is stored inertly in the earth's lithosphere.[3] Much of the carbon stored in the earth's mantle was stored there when the earth formed.[4] Some of it was deposited in the form of organic carbon from the biosphere.[3] Of the carbon stored in the geosphere, about 80% is limestone and its derivatives, which form from the sedimentation of calcium carbonate stored in the shells of marine organisms. The remaining 20% is stored as kerogens formed through the sedimentation and burial of terrestrial organisms under high heat and pressure. Organic carbon stored in the geosphere can remain there for millions of years.[5]

Carbon can leave the geosphere in several ways. Carbon dioxide is released during the metamorphosis of carbonate rocks when they are subducted into the earth's mantle. This carbon dioxide can be released into the atmosphere and ocean through volcanoes and hotspots.[4] It can also be removed by humans through the direct extraction of kerogens in the form of fossil fuels. After extraction, fossil fuels are burned to release energy, thus emitting the carbon they store into the atmosphere

Deep carbon cycle

Although deep carbon cycling is not as well-understood as carbon movement through the atmosphere, terrestrial biosphere, ocean, and geosphere, it is nonetheless an incredibly important process. The deep carbon cycle is intimately connected to the movement of carbon in the Earth's surface and atmosphere. If the process did not exist, carbon would remain in the atmosphere, where it would accumulate to extremely high levels over long periods of time.[6] Therefore, by allowing carbon to return to the Earth, the deep carbon cycle plays a critical role in maintaining the terrestrial conditions necessary for life to exist.

Furthermore, the process is also significant simply due to the massive quantities of carbon it transports through the planet. In fact, studying the composition of basaltic magma and measuring carbon dioxide flux out of volcanoes reveals that the amount of carbon in the mantle is actually greater than that on the Earth's surface by a factor of one thousand.[4] Drilling down and physically observing deep-Earth carbon processes is evidently extremely difficult, as the lower mantle and core extend from 660 to 2,891 km and 2,891 to 6,371 km deep into the Earth respectively. Accordingly, not much is conclusively known regarding the role of carbon in the deep Earth. Nonetheless, several pieces of evidence—many of which come from laboratory simulations of deep Earth conditions—have indicated mechanisms for the element's movement down into the lower mantle, as well as the forms that carbon takes at the extreme temperatures and pressures of said layer. Furthermore, techniques like seismology have led to a greater understanding of the potential presence of carbon in the Earth's core.

Carbon in the Lower Mantle[edit]

Carbon principally enters the mantle in the form of carbonate-rich sediments on tectonic plates of ocean crust, which pull the carbon into the mantle upon undergoing subduction. Not much is known about carbon circulation in the mantle, especially in the deep Earth, but many studies have attempted to augment our understanding of the element's movement and forms within said region. For instance, a 2011 study demonstrated that carbon cycling extends all the way to the lower mantle. The study analysed rare, super-deep diamonds at a site in Juina, Brazil, determining that the bulk composition of some of the diamonds' inclusions matched the expected result of basalt melting and crytallisation under lower mantle temperatures and pressures.[4] Thus, the investigation's findings indicate that pieces of basaltic oceanic lithosphere act as the principle transport mechanism for carbon to Earth's deep interior. These subducted carbonates can interact with lower mantle silicates, eventually forming super-deep diamonds like the one found.[6]

However, carbonates descending to the lower mantle encounter other fates in addition to forming diamonds. In 2011, carbonates were subjected to an environment similar to that of 1800 km deep into the Earth, well within the lower mantle. Doing so resulted in the formations of magnesite, siderite, and numerous varieties of graphite.[4] Other experiments—as well as petrologic observations—support this claim, indicating that magnesite is actually the most stable carbonate phase in most part of the mantle. This is largely a result of its higher melting temperature.[7] Consequently, scientists have concluded that carbonates undergo reduction as they descend into the mantle before being stabilised at depth by low oxygen fugacity environments. Magnesium, iron, and other metallic compounds act as buffers throughout the process.[8] The presence of reduced, elemental forms of carbon like graphite would indicate that carbon compounds are reduced as they descend into the mantle.

Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that polymorphism alters carbonate compounds' stability at different depths within the Earth. To illustrate, laboratory simulations and density functional theory calculations suggest that tetrahedrally coordinated carbonates are most stable at depths approaching the core–mantle boundary.[9][10] A 2015 study indicates that the lower mantle's high pressure causes carbon bonds to transition from sp2 to sp3 hybridised orbitals, resulting in carbon tetrahedrally bonding to oxygen.[11] CO3 trigonal groups cannot form polymerisable networks, while tetrahedral CO4 can, signifying an increase in carbon's coordination number, and therefore drastic changes in carbonate compounds' properties in the lower mantle. As an example, preliminary theoretical studies suggest that high pressure causes carbonate melt viscosity to increase; the melts' lower mobility as a result of its increased viscosity causes large deposits of carbon deep into the mantle.[12]

Accordingly, carbon can remain in the lower mantle for long periods of time, but large concentrations of carbon frequently find their way back to the lithosphere. This process, called carbon outgassing, is the result of carbonated mantle undergoing decompression melting, as well as mantle plumes carrying carbon compounds up towards the crust.[14] Carbon is oxidised upon its ascent towards volcanic hotspots, where it is then released as CO2. This occurs so that the carbon atom matches the oxidation state of the basalts erupting in such areas.[15]

Carbon in the Core[edit]

Although the presence of carbon in the Earth's core is well-constrained, recent studies suggest large inventories of carbon could be stored in this region. Shear (S) waves moving through the inner core travel at about fifty percent of the velocity expected for most iron-rich alloys.[16] Because the core's composition is believed to be an alloy of crystalline iron and a small amount of nickel, this seismic anomaly indicates the presence of light elements, including carbon, in the core.[17] In fact, studies using diamond anvil cells to replicate the conditions in the Earth's core indicate that iron carbide (Fe7C3) matches the inner core's wave speed and density. Therefore, the iron carbide model could serve as an evidence that the core holds as much as 67% of the Earth's carbon.[18] Furthermore, another study found that in the pressure and temperature condition of the Earth's inner core, carbon dissolved in iron and formed a stable phase with the same Fe7C3 composition—albeit with a different structure from the one previously mentioned.[19] In summary, although the amount of carbon potentially stored in the Earth's core is not known, recent studies indicate that the presence of iron carbides can explain some of the geophysical observations.

Human influence

2 in Earth's atmosphere if half of global-warming emissions are not absorbed.[21][22][23][24]

(NASA computer simulation).

Since the industrial revolution, human activity has modified the carbon cycle by changing its components' functions and directly adding carbon to the atmosphere.[25]

The largest human impact on the carbon cycle is through direct emissions from burning fossil fuels, which transfers carbon from the geosphere into the atmosphere. The rest of this increase is caused mostly by changes in land-use, particularly deforestation.

Another direct human impact on the carbon cycle is the chemical process of calcination of limestone for clinker production, which releases CO

2.[26] Clinker is an industrial precursor of cement.

Humans also influence the carbon cycle indirectly by changing the terrestrial and oceanic biosphere.[27] Over the past several centuries, direct and indirect human-caused land use and land cover change (LUCC) has led to the loss of biodiversity, which lowers ecosystems' resilience to environmental stresses and decreases their ability to remove carbon from the atmosphere. More directly, it often leads to the release of carbon from terrestrial ecosystems into the atmosphere. Deforestation for agricultural purposes removes forests, which hold large amounts of carbon, and replaces them, generally with agricultural or urban areas. Both of these replacement land cover types store comparatively small amounts of carbon so that the net product of the process is that more carbon stays in the atmosphere.

Other human-caused changes to the environment change ecosystems' productivity and their ability to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Air pollution, for example, damages plants and soils, while many agricultural and land use practices lead to higher erosion rates, washing carbon out of soils and decreasing plant productivity.

Humans also affect the oceanic carbon cycle.[28] Current trends in climate change lead to higher ocean temperatures, thus modifying ecosystems.[29][29][29] Also, acid rain and polluted runoff from agriculture and industry change the ocean's chemical composition. Such changes can have dramatic effects on highly sensitive ecosystems such as coral reefs,[30][29][31] thus limiting the ocean's ability to absorb carbon from the atmosphere on a regional scale and reducing oceanic biodiversity globally.

Arctic methane emissions indirectly caused by anthropogenic global warming also affect the carbon cycle and contribute to further warming in what is known as climate change feedback.

On 12 November 2015, NASA scientists reported that human-made carbon dioxide (CO

2) continues to increase, reaching levels not seen in hundreds of thousands of years: currently, the rate carbon dioxide released by the burning of fossil fuels is about double the net uptake by vegetation and the ocean.[30][32][32][29]

References

- ^ Riebeek, Holli (16 June 2011). "The Carbon Cycle". Earth Observatory. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Holmes, Richard (2008). "The Age Of Wonder", Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42222-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Falkowski, P.; Scholes, R. J.; Boyle, E.; Canadell, J.; Canfield, D.; Elser, J.; Gruber, N.; Hibbard, K.; Högberg, P.; Linder, S.; MacKenzie, F. T.; Moore b, 3.; Pedersen, T.; Rosenthal, Y.; Seitzinger, S.; Smetacek, V.; Steffen, W. (2000). "The Global Carbon Cycle: A Test of Our Knowledge of Earth as a System". Science. 290 (5490): 291–296. Bibcode:2000Sci...290..291F. doi:10.1126/science.290.5490.291. PMID 11030643.

- ^ Archer, David (2010). The global carbon cycle. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400837076.

- ^ a b c d Prentice, I.C. (2001). "The carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide". In Houghton, J.T. (ed.). Climate change 2001: the scientific basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergouvernmental Panel on Climate Change. hdl:10067/381670151162165141.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Global Carbon Cycle" (PDF). University of New Hampshire. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Lynch, Patrick (12 November 2015). "GMS: Carbon and Climate Briefing - November 12, 2015". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Goddard Media Studios. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Forster, P.; Ramawamy, V.; Artaxo, P.; Berntsen, T.; Betts, R.; Fahey, D.W.; Haywood, J.; Lean, J.; Lowe, D.C.; Myhre, G.; Nganga, J.; Prinn, R.; Raga, G.; Schulz, M.; Van Dorland, R. (2007). "Changes in atmospheric constituents and in radiative forcing". Climate Change 2007: The Physical Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ^ "Many Planets, One Earth // Section 4: Carbon Cycling and Earth's Climate". Many Planets, One Earth. 4. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ a b O'Malley-James, Jack T.; Greaves, Jane S.; Raven, John A.; Cockell, Charles S. (2012). "Swansong Biospheres: Refuges for life and novel microbial biospheres on terrestrial planets near the end of their habitable lifetimes". International Journal of Astrobiology. 12 (2): 99–112. arXiv:1210.5721. Bibcode:2013IJAsB..12...99O. doi:10.1017/S147355041200047X.

- ^ Brownlee 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Brownlee 2010, p. 94.

- ^ Rice, Charles W. (January 2002). "Storing carbon in soil: Why and how?". Geotimes. 47 (1): 14–17. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Yousaf, Balal; Liu, Guijian; Wang, Ruwei; Abbas, Qumber; Imtiaz, Muhammad; Liu, Ruijia (2016). "Investigating the biochar effects on C-mineralization and sequestration of carbon in soil compared with conventional amendments using the stable isotope (δ13C) approach". GCB Bioenergy. 9 (6): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12401.

- ^ Lal, Rattan (2008). "Sequestration of atmospheric CO

2 in global carbon pools". Energy and Environmental Science. 1: 86–100. doi:10.1039/b809492f. - ^ Li, Mingxu; Peng, Changhui; Wang, Meng; Xue, Wei; Zhang, Kerou; Wang, Kefeng; Shi, Guohua; Zhu, Qiuan (2017). "The carbon flux of global rivers: A re-evaluation of amount and spatial patterns". Ecological Indicators. 80: 40–51. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.04.049.

- ^ Bond-Lamberty, Ben; Thomson, Allison (2010). "Temperature-associated increases in the global soil respiration record". Nature. 464 (7288): 579–582. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..579B. doi:10.1038/nature08930. PMID 20336143.

- ^ Sarmiento, J.L.; Gruber, N. (2006). Ocean Biogeochemical Dynamics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

- ^ Kleypas, J. A.; Buddemeier, R. W.; Archer, D.; Gattuso, J. P.; Langdon, C.; Opdyke, B. N. (1999). "Geochemical Consequences of Increased Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide on Coral Reefs". Science. 284 (5411): 118–120. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..118K. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.118. PMID 10102806.

- ^ Langdon, C.; Takahashi, T.; Sweeney, C.; Chipman, D.; Goddard, J.; Marubini, F.; Aceves, H.; Barnett, H.; Atkinson, M. J. (2000). "Effect of calcium carbonate saturation state on the calcification rate of an experimental coral reef". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 14 (2): 639. Bibcode:2000GBioC..14..639L. doi:10.1029/1999GB001195.

- ^ a b NASA (16 June 2011). "The Slow Carbon Cycle". Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ a b The Carbon Cycle and Earth's Climate Information sheet for Columbia University Summer Session 2012 Earth and Environmental Sciences Introduction to Earth Sciences I

- ^ Berner, Robert A. (November 1999). "A New Look at the Long-term Carbon Cycle" (PDF). GSA Today. 9 (11): 1–6.

- ^ "The Deep Carbon Cycle and our Habitable Planet | Deep Carbon Observatory". deepcarbon.net. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Mark (2003). "Where do Carbon Atoms Reside within Earth's Mantle?". Physics Today. 56 (10): 21–22. Bibcode:2003PhT....56j..21W. doi:10.1063/1.1628990.

- ^ "Carbon cycle reaches Earth's lower mantle: Evidence of carbon cycle found in 'superdeep' diamonds From Brazil". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Stagno, V.; Frost, D. J.; McCammon, C. A.; Mohseni, H.; Fei, Y. (5 February 2015). "The oxygen fugacity at which graphite or diamond forms from carbonate-bearing melts in eclogitic rocks". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 169 (2): 16. Bibcode:2015CoMP..169...16S. doi:10.1007/s00410-015-1111-1. ISSN 1432-0967.

- ^ a b Fiquet, Guillaume; Guyot, François; Perrillat, Jean-Philippe; Auzende, Anne-Line; Antonangeli, Daniele; Corgne, Alexandre; Gloter, Alexandre; Boulard, Eglantine (29 March 2011). "New host for carbon in the deep Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (13): 5184–5187. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5184B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016934108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3069163. PMID 21402927.

- ^ Dorfman, Susannah M.; Badro, James; Nabiei, Farhang; Prakapenka, Vitali B.; Cantoni, Marco; Gillet, Philippe (1 May 2018). "Carbonate stability in the reduced lower mantle". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 489: 84–91. Bibcode:2018E&PSL.489...84D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.02.035. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Kelley, Katherine A.; Cottrell, Elizabeth (14 June 2013). "Redox Heterogeneity in Mid-Ocean Ridge Basalts as a Function of Mantle Source". Science. 340 (6138): 1314–1317. Bibcode:2013Sci...340.1314C. doi:10.1126/science.1233299. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23641060.

- ^ "ScienceDirect". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Mao, Wendy L.; Liu, Zhenxian; Galli, Giulia; Pan, Ding; Boulard, Eglantine (18 February 2015). "Tetrahedrally coordinated carbonates in Earth's lower mantle". Nature Communications. 6: 6311. arXiv:1503.03538. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6E6311B. doi:10.1038/ncomms7311. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 25692448.

- ^ Carmody, Laura; Genge, Matthew; Jones, Adrian P. (1 January 2013). "Carbonate Melts and Carbonatites". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 75 (1): 289–322. Bibcode:2013RvMG...75..289J. doi:10.2138/rmg.2013.75.10. ISSN 1529-6466.

- ^ Dasgupta, Rajdeep (10 December 2011). "From Magma Ocean to Crustal Recycling: Earth's Deep Carbon Cycle".

- ^ Dasgupta, Rajdeep; Hirschmann, Marc M. (15 September 2010). "The deep carbon cycle and melting in Earth's interior". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 298 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.298....1D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.06.039. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Frost, Daniel J.; McCammon, Catherine A. (2008). "The Redox State of Earth's Mantle". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 36: 389–420. Bibcode:2008AREPS..36..389F. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124322.

- ^ "Does Earth's Core Host a Deep Carbon Reservoir? | Deep Carbon Observatory". deepcarbon.net. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "Does Earth's Core Host a Deep Carbon Reservoir? | Deep Carbon Observatory". deepcarbon.net. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ Li, Jie; Chow, Paul; Xiao, Yuming; Alp, E. Ercan; Bi, Wenli; Zhao, Jiyong; Hu, Michael Y.; Liu, Jiachao; Zhang, Dongzhou (16 December 2014). "Hidden carbon in Earth's inner core revealed by shear softening in dense Fe7C3". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (50): 17755–17758. doi:10.1073/pnas.1411154111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4273394. PMID 25453077.

- ^ Hanfland, M.; Chumakov, A.; Rüffer, R.; Prakapenka, V.; Dubrovinskaia, N.; Cerantola, V.; Sinmyo, R.; Miyajima, N.; Nakajima, Y. (March 2015). "High Poisson's ratio of Earth's inner core explained by carbon alloying". Nature Geoscience. 8 (3): 220–223. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..220P. doi:10.1038/ngeo2370. ISSN 1752-0908.

- ^ a b Buis, Alan; Ramsayer, Kate; Rasmussen, Carol (12 November 2015). "A Breathing Planet, Off Balance". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ a b Staff (12 November 2015). "Audio (66:01) - NASA News Conference - Carbon & Climate Telecon". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ a b St. Fleur, Nicholas (10 November 2015). "Atmospheric Greenhouse Gas Levels Hit Record, Report Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b Ritter, Karl (9 November 2015). "UK: In 1st, global temps average could be 1 degree C higher". AP News. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ IPCC (2007) 7.4.5 Minerals Archived 25 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Climate Change 2007: Working Group III: Mitigation of Climate Change,

- ^ a b Morse, John W.; Morse, John W. Autor; Morse, John W.; MacKenzie, F. T.; MacKenzie, Fred T. (1990). "Chapter 9 the Current Carbon Cycle and Human Impact". Geochemistry of Sedimentary Carbonates. Developments in Sedimentology. 48. pp. 447–510. doi:10.1016/S0070-4571(08)70338-8. ISBN 9780444873910.

- ^ Laws, Edward A.; Falkowski, Paul G.; Smith, Walker O.; Ducklow, Hugh; McCarthy, James J. (2000). "Temperature effects on export production in the open ocean". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 14 (4): 1231–1246. Bibcode:2000GBioC..14.1231L. doi:10.1029/1999GB001229.

- ^ Takahashi, Taro; Sutherland, Stewart C.; Sweeney, Colm; Poisson, Alain; Metzl, Nicolas; Tilbrook, Bronte; Bates, Nicolas; Wanninkhof, Rik; Feely, Richard A.; Sabine, Christopher; Olafsson, Jon; Nojiri, Yukihiro (2002). "Global sea–air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects". Deep Sea Research Part Ii: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 49 (9–10): 1601–1622. doi:10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00003-6.

- ^ Sanford, E. (1999). "Regulation of Keystone Predation by Small Changes in Ocean Temperature". Science. 283 (5410): 2095–2097. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.2095S. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2095.

- ^ Kleypas, J. A.; Buddemeier, Robert W.; Archer, David; Gattuso, Jean-Pierre; Langdon, Chris; Opdyke, Bradley N. (1999). "Geochemical Consequences of Increased Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide on Coral Reefs". Science. 284 (5411): 118–120. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..118K. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.118.

- ^ Hughes, T. P.; Baird, A. H.; Bellwood, D. R.; Card, M.; Connolly, S. R.; Folke, C.; Grosberg, R.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jackson, J. B.; Kleypas, J.; Lough, J. M.; Marshall, P.; Nyström, M.; Palumbi, S. R.; Pandolfi, J. M.; Rosen, B.; Roughgarden, J. (2003). "Climate Change, Human Impacts, and the Resilience of Coral Reefs". Science. 301 (5635): 929–933. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..929H. doi:10.1126/science.1085046. PMID 12920289.

- ^ Orr, James C.; Fabry, Victoria J.; Aumont, Olivier; Bopp, Laurent; Doney, Scott C.; Feely, Richard A.; Gnanadesikan, Anand; Gruber, Nicolas; Ishida, Akio; Joos, Fortunat; Key, Robert M.; Lindsay, Keith; Maier-Reimer, Ernst; Matear, Richard; Monfray, Patrick; Mouchet, Anne; Najjar, Raymond G.; Plattner, Gian-Kasper; Rodgers, Keith B.; Sabine, Christopher L.; Sarmiento, Jorge L.; Schlitzer, Reiner; Slater, Richard D.; Totterdell, Ian J.; Weirig, Marie-France; Yamanaka, Yasuhiro; Yool, Andrew (2005). "Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms". Nature. 437 (7059): 681–686. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..681O. doi:10.1038/nature04095. PMID 16193043.

Further reading

- Appenzeller, Tim (February 2004). "The case of the missing carbon". National Geographic Magazine. (Article about the missing carbon sink.)

- Bolin, Bert; Degens, E. T.; Kempe, S.; Ketner, P. (1979). The global carbon cycle. Chichester ; New York: Published on behalf of the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) by Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-99710-8. Archived from the original on 28 October 2002. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- Houghton, R. A. (2005). "The contemporary carbon cycle". In William H Schlesinger (ed.). Biogeochemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 473–513. ISBN 978-0-08-044642-4.

- Janzen, H. H. (2004). "Carbon cycling in earth systems—a soil science perspective". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 104 (3): 399–417. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.622. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2004.01.040.

- Millero, Frank J. (2005). Chemical Oceanography (3 ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-2280-8.

- Volk, Tyler; Hoffert, Martin I. (1985). "Ocean Carbon Pumps: Analysis of Relative Strengths and Efficiencies in Ocean‐Driven Atmospheric CO2 Changes". In Sundquist, Eric; Broecker, Wallace S. (eds.). The Carbon cycle and atmospheric CO₂ natural variations, Archean to present. Washington DC American Geophysical Union Geophysical Monograph Series. 32. p. 99. Bibcode:1985GMS....32...99V. doi:10.1029/GM032p0099. ISBN 978-1-118-66432-2.

External links

- Carbon Cycle Science Program – an interagency partnership.

- NOAA's Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases Group

- Global Carbon Project – initiative of the Earth System Science Partnership

- UNEP – The present carbon cycle – Climate Change carbon levels and flows

- NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory

- CarboSchools, a European website with many resources to study carbon cycle in secondary schools.

- Carbon and Climate, an educational website with a carbon cycle applet for modeling your own projection.

Carbon cycle

Content

Carbon cycle

External Media

Carbon cycle

Cataloging

- Public domain

- File: File:Carbon cycle.jpg

- Created: 6 May 2012

- Public domain

- File: File:Carbon dioxide emissions global carbon cycle.jpg

- Created: 12 Nov 2015

2 and water from the atmosphere for living and growing.

- Public domain

- File: File:Epífitas en los cables de la luz eléctrica.JPG

- Created: 2 Aug 2008

- Fair use

- File: File:Carbon cycle human perturbation.png

2 in Earth's atmosphere if half of global-warming emissions are not absorbed.[41][42][43][44]

(NASA computer simulation).

- Public domain

- File: File:M15-162b-EarthAtmosphere-CarbonDioxide-FutureRoleInGlobalWarming-Simulation-20151109.jpg

- Created: 9 Nov 2015

No comments

Post a Comment